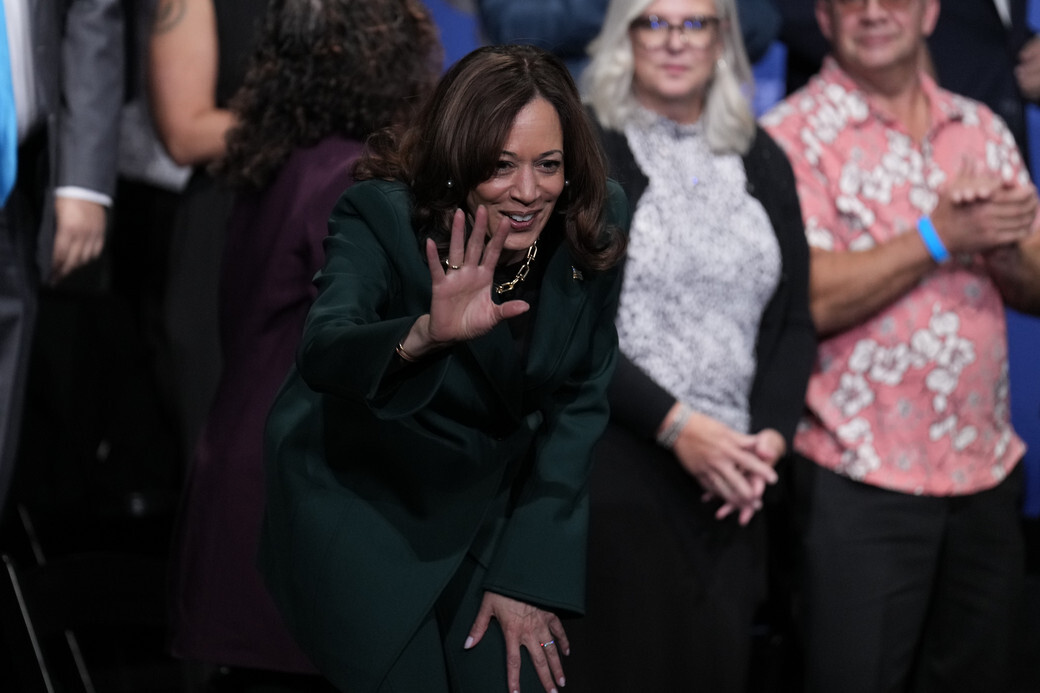

As the U.S. election looms, Europeans are closely watching to see if the winner will be Donald Trump or Kamala Harris. For many, Trump’s return would be a troubling outcome due to his unpredictable stance on foreign alliances, particularly NATO, while Harris, with her commitment to global cooperation, is viewed as a stabilizing force.

However, despite the anxiety surrounding the election, Europeans may be missing a larger issue: the U.S. has been gradually disengaging from Europe for decades, a trend that likely won’t change regardless of who wins.

America’s waning interest in Europe is apparent not only in political and military terms but also culturally and economically. As Washington focuses increasingly on the Indo-Pacific, the significance of Europe in American strategy has shrunk.

Even President Biden, a firm supporter of NATO and Ukraine, has prioritized the Asia-Pacific region, evidenced by the controversial AUKUS alliance with Australia and the U.K. For many in Washington, Europe is now seen as secondary, useful primarily as an ally but not central to America’s core interests.

The close partnership between the U.S. and Europe that flourished after World War II and reached its peak in the 1990s has since faded. This era, marked by U.S.-led initiatives like Desert Storm and cultural exports like the “Dream Team” in the Olympics, showcased America’s powerful presence in Europe. But today, the U.S. military footprint in Europe is reduced, and American influence in culture and media has declined as digital giants like Meta and X dominate without the glamour of earlier U.S. brands.

Some policymakers in Washington, like former U.S. Army commander Ben Hodges, argue that Europe still offers the U.S. strategic benefits far outweighing the costs. However, the newer generation of U.S. officials, who often focus on Asia or Latin America, seems less invested in Europe’s security. This shift is partly due to demographic changes and a broader prioritization of U.S. resources elsewhere, leaving Europe feeling increasingly sidelined.

Europe Faces Uncertain Future as U.S. Engagement Declines Amid Election Between Trump and Harris

The U.S.-EU economic relationship remains substantial, but political shifts in the U.S. are straining transatlantic ties. Notably, Republicans like Trump and his allies view NATO and Europe’s defense needs as secondary to U.S. domestic concerns, fueling fears of a more isolationist America. Despite attempts by European leaders to maintain strong ties, like Poland’s push to emphasize mutual benefits, the divide between American interests and Europe’s needs seems to be widening.

For European leaders, the prospect of a Trump presidency raises the risk of unpredictable policies, especially regarding NATO and trade. Trump has previously criticized NATO as a burden and might seek to reduce U.S. commitments in Europe. In contrast, a Harris administration would likely continue supporting NATO and Ukraine, though her focus would still lean toward Asia. Regardless, Europe must prepare for a reality where U.S. engagement in European defense may no longer be guaranteed.

France has been a vocal advocate for Europe’s strategic autonomy, urging the EU to take charge of its defense rather than depending on U.S. voters. French leaders like Europe Minister Benjamin Haddad argue that Europe’s security shouldn’t hinge on America’s internal politics. Despite this, there is little momentum within the EU to establish a European military or cohesive defense strategy, as internal divisions persist over how Europe should achieve autonomy.

Many Eastern and Northern European nations, for example, fear that strategic autonomy is merely a way for France and Germany to dominate EU defense policies. Some, especially those closest to Russia, are concerned that without U.S. support, they’d be vulnerable to Russian aggression. Thus, strategic autonomy remains a divisive concept, and EU states lack a united approach to building a self-reliant defense system.

Should Trump win, Europe’s need for self-reliance would intensify, as many fear he might distance the U.S. from European defense entirely. However, there’s also a risk that rather than uniting, EU nations would adopt an “every nation for itself” approach, seeking separate alliances with superpowers like China and Russia. Such fragmentation would weaken Europe’s collective security and bargaining power, exposing it to further external threats.

As the U.S. drifts toward the Asia-Pacific, Europe faces a pivotal moment in its relationship with America. If the EU fails to adapt to a less supportive U.S., it risks losing its footing on the global stage. Without decisive action to strengthen its own defense and unity, Europe may find itself sidelined in a multipolar world, vulnerable to the very risks it once relied on the U.S. to counter.