The Achrafieh neighborhood in Beirut, known for its predominantly Christian population, is currently experiencing the sounds of war from the Israeli airstrikes targeting the southern suburbs. Despite the ongoing conflict, the streets remain quiet, with volunteers patrolling to maintain security and reassure residents.

This neighborhood watch was established in response to the rising crime rates during Lebanon’s financial crisis, but its purpose has shifted recently to address concerns regarding the large influx of displaced families from southern Lebanon, particularly those fleeing the violence associated with Israel’s air campaign against Hezbollah.

The arrival of displaced people, primarily from Shia Muslim areas like Dahieh and the Bekaa Valley, has raised fears of exacerbating existing sectarian tensions in a country still haunted by its civil war memories. Local communities are attempting to support the hundreds of thousands of families displaced by the conflict, yet the increased presence of these families has sparked suspicion and concern among some residents.

Notably, a deadly airstrike in Aitou, which killed displaced individuals, has intensified apprehensions within the Christian community regarding the potential presence of Hezbollah members among the newcomers.

As the situation evolves, some residents express discomfort with the influx of Shia families, fearing they could be targeted by Israeli forces. Building management firms have begun requesting detailed information from tenants about their guests, including identity and vehicle details.

Achrafieh Neighborhood Faces Tensions Amid Israeli Airstrikes and Influx of Displaced Families from Southern Lebanon

In certain areas, flyers have been circulated urging Hezbollah members to leave, reflecting the rising tensions and fears among residents who worry about security implications and the possible escalation of conflict in their neighborhoods.

Historical context plays a significant role in these dynamics, as Lebanon’s civil war (1975-1990) was marked by violent sectarian conflict between various militias. The remnants of these tensions persist today, as residents recall the control exerted by sectarian militias.

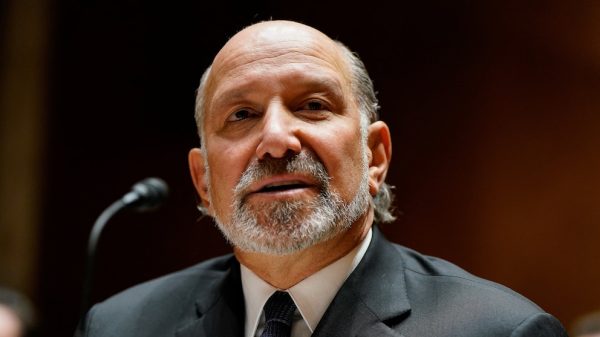

Nadim Gemayel, the founder of the neighborhood watch, emphasizes the need for security and awareness in the current climate while advocating for disarmament of groups like Hezbollah, whom he believes have contributed to the ongoing turmoil.

In contrast, the mixed neighborhood of Hamra is experiencing a different reality as schools and empty buildings are repurposed to shelter displaced families, many from the Shia community.

This rapid influx has led to tensions between landlords and new arrivals, with some property owners fearing that the displaced families might refuse to leave after the war ends. One resident described the situation in her building, noting a dramatic increase in the number of people squatting, which has altered the social fabric of the area.

Fatima al-Haj Yousef, a mother from the Bekaa Valley, reflects on the challenges faced by displaced families, including the struggle for basic needs and the fear of eviction. While some residents express acceptance and support for the newcomers, others harbor suspicions and resentment, indicating potential sectarian divides.

The complexities of these interactions highlight the fragility of social dynamics in Beirut, as the ongoing conflict and the presence of Hezbollah complicate the path to stability and peace in the region.