Evan Hafer, a well-known veteran and the founder of Black Rifle Coffee, appeared on Joe Rogan’s podcast following the November election. Like many supporters of the Maga movement, the US-Mexico border was a key issue on his mind.

“If we declare war on the cartel, these guys won’t know what hit them. They are in for a world of ultra-violence,” said Hafer, who previously served in the Green Berets and the CIA.

“JD [Vance] or Trump mentioned something with the new guy from Ice, saying: ‘We’re going to deploy tier one units against the cartel.’”

Hafer was referring to some of the most elite and secretive units within the American special forces, predicting that the war on drugs could escalate into a full-scale military operation inside Mexico.

This would involve targeting major narcotics-trafficking organizations like the Sinaloa and Jalisco cartels using the same elite forces deployed in the war on terror.

“Yes, that is a real possibility,” he confirmed.

While it sounded like a plot straight out of Sicario, Hafer’s remarks gained millions of views on YouTube. This raises the question: what would such military action south of the border truly cost the United States?

That scenario is no longer hypothetical.

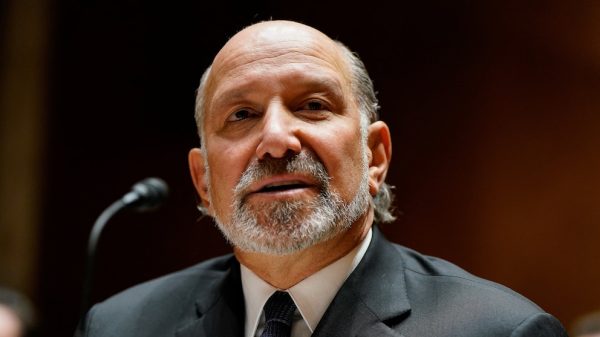

John P. Sullivan, a senior fellow at the Small Wars Journal-El Centro, cautioned against unilateral US military intervention in Mexico, calling it a dangerous proposition.

One of Donald Trump’s first executive orders on Monday officially designated Mexican cartels as terrorist organizations, grouping them alongside al-Qaida and the Islamic State (Isis)—long-standing enemies in over two decades of costly and bloody American conflicts.

Days later, the Pentagon followed up by announcing the deployment of 1,500 active-duty troops to the border. However, experts warn that any American military intervention in Mexico could trigger serious repercussions.

Mexican cartels, heavily armed due to the flow of US weapons, are known for their ruthless retaliatory violence. Ordinary Americans could be caught in the crossfire, particularly tourists in destinations like Cancún, where cartel influence is already entrenched, as well as communities along the US-Mexico border.

“The ongoing talk of unilateral US military intervention in Mexico is extremely risky,” said Sullivan, who previously worked in law enforcement in Los Angeles.

He pointed out that, from a legal perspective, the special designation does not automatically authorize military action. However, labeling cartel activities and immigration as an invasion could be a calculated move to justify direct military engagement.

Lucas Webber, a senior threat intelligence analyst at Tech Against Terrorism, echoed similar concerns. “Cartels may retaliate by attacking soft targets such as tourists, diplomatic personnel in Mexico, or even the troops being deployed at the US border,” he warned. “They could also leverage networks inside the US itself.”

The kind of operations described by Hafer and Trump—who has hinted that deploying special forces on Mexican soil “could happen”—mirror past missions against Isis and al-Qaida.

Those campaigns relied on elite units, such as Seal Team 6, which carried out the 2011 raid that killed Osama bin Laden in Pakistan, along with targeted aerial strikes to dismantle terror networks.

US intelligence previously compiled “kill lists” of targets, which the US Special Operations Command (Socom) systematically eliminated.

These operations cost billions of dollars, resulted in widespread civilian casualties, and inadvertently fueled the growth of Isis by radicalizing new recruits.

Mexican Cartels

“Politically, targeting cartel leadership with ‘kingpin’ operations is appealing, but operationally, it’s extremely risky,” said Sullivan.

“Ousting cartel leaders often creates power vacuums, triggering violent infighting among rival factions competing for control. This only escalates instability and bloodshed.”

For now, Socom will not be involved in Trump’s initial deployment of soldiers to the southern border.

“There are no Socom troops being deployed for this mission,” a Socom public affairs officer stated in response to inquiries from The Guardian.

Both Barack Obama and Trump had previously considered designating cartels as terrorist groups but ultimately backed down. However, in 2020, Trump suggested launching missile strikes inside Mexico.

Declaring outright war on Mexican cartels would have profound consequences for the country’s infrastructure. The drug trade is believed to be one of Mexico’s largest employers, contributing billions to its economy.

Many politicians, military officials, law enforcement officers, and business leaders are suspected of being on cartel payrolls. Cartels also enjoy local support in certain regions, operating as a shadow narco-state.

Furthermore, should the US military act on its threats, retaliation from these criminal organizations—known for beheadings and brutal executions—could be severe.

Since 9/11, cartels have significantly upgraded their arsenals, sometimes with US-supplied weapons. Some are now in possession of Javelin missile launchers, armored vehicles, and highly trained former commandos.

“There is a real possibility that airstrikes and raids could eventually be carried out,” Webber noted.

He added that cartels have studied modern conflicts in Ukraine and Syria, adapting their tactics accordingly. Some have also enhanced their drone capabilities and expanded operations in other strategic areas.

“This shows how adaptable and evolving Mexican cartels have become,” Webber explained. Sullivan, however, remained skeptical that American civilians in Mexico faced an immediate threat.

“Mexican cartels have long used terrorist-style tactics to assert dominance and influence state actions,” he said. “However, attacks specifically targeting American tourists are uncommon.”

He noted that while cartels and gangs typically avoid direct confrontations with US law enforcement, they have a well-documented history of targeting Mexican law enforcement, judicial officials, mayors, legislators, and journalists.

Taking cues from Isis, Mexican cartels aggressively use social media to promote their violent exploits. Through platforms like Telegram and WhatsApp, they circulate videos of gruesome executions to intimidate communities and warn government authorities.

“Cartels are leveraging various social media and messaging apps to recruit members, spread fear, and showcase their power,” Webber added. “They use these platforms to target journalists, politicians, informants, and prosecutors.”