Donald Trump is set to encounter strong opposition from Jordan’s King Abdullah at the White House today in their first meeting since the former U.S. president suggested relocating Gaza’s population to Jordan.

As a key U.S. ally, Jordan has been navigating a delicate balance between its military and diplomatic ties with Washington and widespread domestic support for the Palestinians.

These tensions, already exacerbated by the Gaza War, are being pushed to a critical point by Trump’s proposed approach to Gaza’s future.

Expanding on his previous remarks, Trump has insisted that Gazans should be resettled in Jordan and Egypt, telling a Fox News anchor that they would be permanently denied the right to return home. If enforced, such a policy would violate international law.

On Monday, he went further, stating that he might cut off aid to Jordan and Egypt if they refused to accept Palestinian refugees.

Some of the most vocal opponents of relocating Gazans to Jordan are those who had already made the move decades ago.

Roughly 45,000 people live in Gaza Camp, a refugee settlement near Jordan’s northern town of Jerash—one of several Palestinian refugee camps in the country.

In the camp’s narrow alleyways, sheets of corrugated iron serve as makeshift roofs over small shopfronts, while children ride donkeys through the crowded market streets.

Every family here traces its origins back to Gaza—to Jabalia, Rafah, Beit Hanoun. Most fled following the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, believing their displacement would be temporary. Decades later, they remain.

Maher Azazi, 60, left Gaza with his family when he was three years old

“Donald Trump is an arrogant narcissist,” says Maher Azazi, now 60. “He has a medieval mentality, the mindset of a tradesman.”

Maher left Jabalia as a toddler, but some of his relatives still live there, now sifting through the wreckage of their home in search of 18 missing family members.

Despite the devastation, Mr. Azazi believes most Gazans today have learned from past generations and would rather risk their lives than leave.

Those who once viewed displacement as a temporary refuge now see it as aiding Israel’s far-right nationalists in their bid to claim Palestinian land.

“We Gazans have seen this before,” says Yousef, who was born in the camp. “Back then, they told us it was only temporary, that we would return. The right to return is a red line.”

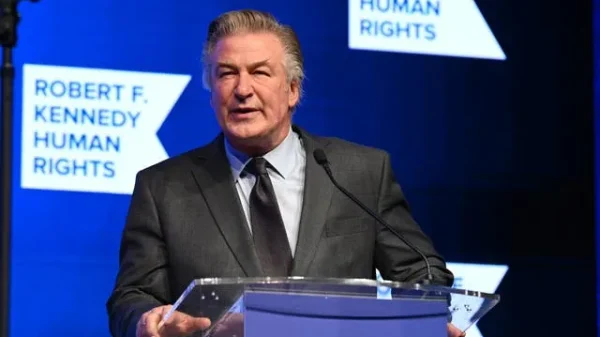

Donald Trump Meets King Abdullah

Another resident, recalling his family’s past, adds: “When our ancestors left, they had no weapons, unlike Hamas today. But now, the younger generation understands what happened, and it won’t be repeated. Now there is resistance.”

Jordan has long been a refuge for those fleeing conflicts across the Middle East, cementing its status as a small yet strategically significant nation.

In the early 2000s, Iraqis arrived seeking safety from war. A decade later, Syrians followed, leading Jordan’s king to warn that the country was at “boiling point.”

Many native Jordanians blame successive waves of refugees for rising unemployment and poverty. At a food bank near a central Amman mosque, volunteers distribute 1,000 meals daily.

Outside the mosque, Imad Abdallah and his friend Hassan, both unemployed day laborers, wait in vain for work.

“The situation in Jordan used to be good,” says Hassan. “But after the Iraq war, it worsened. Then came the Syrian war, and it got worse. Now, with Gaza’s war, it’s even worse. Every war around us makes things harder because we always help and take in people.”

Imad, struggling to support his four children, is more direct.

“The foreigners take our jobs,” he says. “I’ve been unemployed for four months. No money, no food. If Gazans come, we will starve.”

However, Jordan is also under pressure from its closest military ally. Trump has already suspended over $1.5 billion in annual U.S. aid to the country. Many Jordanians anticipate an escalating confrontation between their leaders and the new U.S. president.

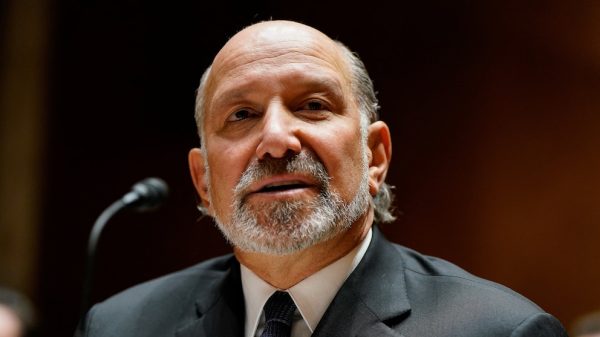

Jawad Anani, a former deputy prime minister with close ties to the Jordanian government, predicts that King Abdullah will deliver a blunt message to Trump during their meeting.

“We consider any attempt by Israel or others to expel people from their homes in Gaza and the West Bank a criminal act,” Anani says. “And any effort to push those people into Jordan would be tantamount to a declaration of war.”

Even if Gazans were willing to relocate voluntarily as part of a broader Middle East agreement, he argues, trust is completely absent.

“There is no confidence,” he says. “As long as Netanyahu and his government are involved, no promise from anyone can be trusted. Period.”

Trump’s insistence on reshaping Gaza’s future may force a key U.S. ally into an impossible choice.

Last Friday, thousands of Jordanians took to the streets to protest Trump’s proposal.

Jordan hosts U.S. military bases, millions of refugees, and plays a critical role in regional security cooperation—especially as Israel watches for smuggling routes into the occupied West Bank.

Any threat to Jordan’s stability is a threat to its allies as well. If stability is Jordan’s greatest strength, the risk of unrest remains its most potent leverage—and its ultimate shield.