Preserving water has remained a crucial challenge for many nations over time. As modern technologies strain under growing environmental concerns and rapid population increases, attention is turning back to age-old knowledge systems.

Across regions, traditional water management solutions are gaining renewed attention as communities seek alternatives to industrial systems that are expensive to maintain and often harmful to ecosystems.

Rooftops turning into lifelines during dry seasons (Photo: Twitter)

One of the countries bringing this heritage back into active use is a South Asian giant, where centuries-old methods are being studied, revived, and implemented once again with fresh relevance.

Many rural and urban areas alike are returning to systems their ancestors used to manage rainfall, recharge groundwater, and store excess supplies for periods of drought.

These time-tested strategies had been pushed aside for modern infrastructure, yet communities are now seeing the wisdom in restoring these historical techniques. From rooftop rainwater collection to stepwells, from tankas to johads, there is a renewed interest in ensuring water availability for agriculture, daily use, and survival in dry spells.

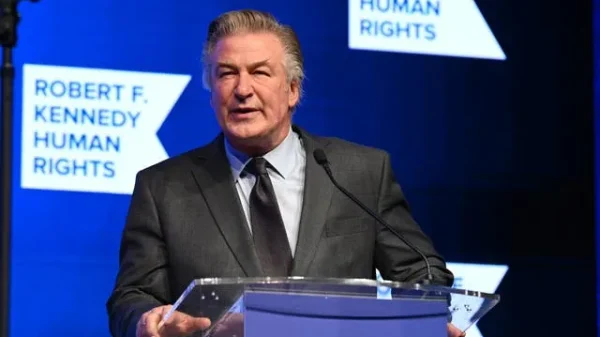

Rainwater Harvesting Through Rooftop Collection

Among the renewed approaches is rooftop rainwater collection, which has seen a return in homes, schools, and office buildings. This method involves directing rainfall from rooftops through pipes into storage tanks, allowing for the collection and use of water during dry periods.

Unlike many current systems dependent on rivers or boreholes, this method provides an individual or household with a personal supply. Cities where rainfall can be heavy but infrequent are especially benefiting from this practice. Many housing colonies have begun adopting this system again, reducing pressure on public water networks.

In some regions, local governments have even introduced regulations to ensure new constructions come equipped with rooftop collection systems. The stored water is used for washing, cleaning, and sometimes drinking if properly treated. By going back to these approaches, water scarcity issues are being addressed without heavy reliance on external technologies.

The Role of Stepwells in Dry Regions

Stepwells, often admired for their architectural beauty, were once essential for survival in dry regions. These large wells with stairs leading down to the water level allowed access even when the water was low.

Constructed mostly in areas with scant rainfall, they served as vital water sources for centuries. Some date back over a thousand years and are still in usable condition after restoration.

These structures are now being cleaned, repaired, and put back to use in villages and towns where groundwater has receded due to over-extraction. In some cases, they are also serving as rainwater recharge systems, allowing rain to seep through the ground and refill underground aquifers. Reviving these facilities has brought life back to certain rural settlements that previously faced long walks just to fetch water.

Traditional Tank Systems

The tank system, known in many regions by different names, remains one of the most effective methods of storing water during the rainy season for use during dry months.

These are often shallow, human-made ponds or basins that collect surface runoff. They were once common in southern parts of the country and served agricultural communities that depended on monsoon rainfall.

Over time, many of these tanks were neglected, encroached upon, or filled with garbage. Today, several regional governments and non-profit organisations are partnering with residents to restore them.

By desilting the tanks and clearing their channels, large volumes of water are once again being held locally. As a result, farmers are witnessing improved crop yields and a more predictable water supply during difficult months.

Johads and Check Dams as Community Solutions

Johads are another traditional method that involved constructing small earthen check dams to collect and hold rainwater. They recharge groundwater levels and also serve livestock and local agricultural needs.

Found mainly in arid zones, especially in western parts of the country, johads are often constructed with local materials, making them cost-effective and sustainable.

Villagers have come together to rebuild and maintain these community assets. This has improved access to water within walking distance for households and farms. Additionally, the creation of johads has helped reverse the drying up of nearby wells and hand pumps, once considered a major concern for village women and children who had to travel long distances.

Check dams, which operate on a similar principle, have also returned to favour. These small barriers across streams help reduce water flow speed, encouraging water to seep into the ground and recharge aquifers.

As groundwater levels rise again, farming communities gain back the confidence to grow water-intensive crops that had previously been abandoned due to lack of supply.

Tankas: A Desert Region Solution

In desert areas, tankas represent one of the oldest water-saving solutions. These underground storage systems collect rainwater through small inlets and store it in lined chambers that can last through many months of dry weather. These were usually constructed near homes and sometimes shared by several families.

Modern adaptations of tankas now include improved filtration systems and coverings to prevent contamination. In areas where groundwater is saline and unsuitable for drinking, tankas are especially helpful. Their simplicity and low maintenance costs make them an ideal choice for regions where larger systems are neither practical nor affordable.

Community workshops are teaching younger generations how to build and maintain tankas, passing on this knowledge which had nearly disappeared. These sessions are supported by local leaders who see water preservation as vital for their communities’ survival.

Water Temples and Sacred Ponds

Certain water bodies once served both religious and practical roles. Temples were built around ponds or springs, and these were maintained as part of religious duties. Though their primary role was spiritual, they also acted as community water sources. Over time, many dried up due to neglect or pollution.

Now, conservationists and heritage enthusiasts are working with religious authorities to bring life back to these sacred water points. Cleaning the ponds, restoring the stone steps, and encouraging rainwater entry have made them useful again. This approach combines faith-based involvement with environmental goals, helping people take ownership of the project.

Such efforts have encouraged the upkeep of these spaces, promoting both cultural values and sustainability. They also serve as examples of how faith-based organisations can play a role in environmental care.

Community Participation and Youth Engagement

Restoring traditional water systems cannot happen without the people who live around them. Community participation has been a strong part of many of these revivals. From digging out silted tanks to planting trees around catchment areas, local involvement helps ensure that the systems will be maintained long after the initial project ends.

Schoolchildren are being introduced to these ideas through environmental clubs and practical lessons. Many schools now teach the importance of water conservation by involving students in projects that build small models of johads or stepwells. Youth-led groups in cities have also begun helping to install rooftop rain collection systems, spreading awareness while making a difference.

This blend of old methods and new energy from younger generations has given momentum to the restoration work. Where government funding is limited, local support has often filled the gap.

Traditional Knowledge Combined with Scientific Understanding

Though these water systems were developed long ago, present-day engineers and hydrologists are studying them carefully. In some cases, scientific tools are helping improve these traditional structures. For example, computer models are used to determine the best location for new johads or tanks.

A return to stepwells and tankas sparks new hope (Photo: Alamy)

This combination of traditional techniques with modern analysis ensures that restored systems perform better and last longer. It also strengthens the credibility of these systems in the eyes of planners who may have previously dismissed them as outdated.

There is growing respect for the engineering wisdom of previous generations, who designed structures suited perfectly to their environment without relying on external resources. The cooperation between scientists and villagers has strengthened trust and improved outcomes.

Environmental Benefits Beyond Water Storage

These revived water systems do more than just store water. They also improve the local environment. By raising the water table, they help revive vegetation and support biodiversity. Animals that had disappeared due to dryness are returning to some regions.

In agricultural zones, soil quality improves with better moisture retention, leading to better harvests and fewer fertiliser needs. The shade from planted trees near tanks or ponds also cools the air, reducing heat effects in nearby areas.

Birds and fish have returned to places that had become barren, helping restore local ecosystems. These results show that water restoration efforts bring multiple rewards, improving quality of life on many levels.

Preserving Knowledge for Future Generations

As interest grows in traditional methods, more efforts are being made to document and preserve this knowledge. Oral histories, drawings, and videos are being used to record the details of how ancient systems were built and maintained. Universities are including these techniques in environmental engineering studies, making sure the knowledge passes on.

Workshops and exhibitions are helping rural elders share their knowledge with students, architects, and policy makers. These exchanges encourage mutual respect between generations and spark new ideas for water planning.

The return of these methods shows that answers to today’s challenges sometimes lie in the past. By valuing traditional knowledge and adapting it to present needs, communities are finding reliable ways to manage their water supply with minimal waste and greater resilience.